"how our ears hear them" - it’s not just that, it will also depend in part on the audio equipment that people use, and there will be a large variation in that area. eRightSoft’s “SUPER ©” media converter is one of the most useful freebies I use - I don’t know whether you know it, but it’s very comprehensive and has apparently been written by geeks for geeks. It would be easier for people to try the experiment for themselves, as long as they’ve got a sound editor with a spectral analyzer. That, and the information in the inbuilt mp3 tags, would be a dead give-away.

128 KBPS VS 320 KBPS 320KBPS

But there is the possibility that the other site might alter the sound files - putting them into another format, for example.Īlso, the size of an mp3 file is directly related to its bit rate: the 32kbps file, for instance, is 40KB, while the 320kbps file is 388KB. I can’t post them here (as far as I know), so that leaves other sites like Sound Lantern. Posting the clips - an interesting thought but I doubt its practicality. Summary: 192kbps and above gives best audio results 128 is ok for web use and if you’re not too worried about a little bit of distortion, and 32kbps can have an unexpected use in transcribing tunes. This means you lose a lot of the clutter of hiss and high harmonics the tune notes therefore sound more distinct and, if you use the spectral frequency option in a sound editor, are very obvious on screen. Convert the recording to 32kbps mp3 and you’ll have a top cut-off frequency of 5kHz (just above the top note on a piano).

This can have an application for someone who records a tune and needs a little help in transcribing it from the recording. This was certainly not so when I subtracted the 128 file from the 320 – the lost frequencies, although still at a relatively low dB level, were certainly audible on playback and are the cause of the audible distortion on 128kbps mp3. These were at a very low dB level and in practical terms would be inaudible. I digitally subtracted the 320kbps file from the 1411kbps file (the original) to generate a difference file consisting of the lost or attenuated frequencies. I did a couple of further experiments to explore this distortion effect. This distortion, as I’ve said above, is apparent when you get down to 128kbps or below, but can be lived with at 192 and above, and certainly with 320kbps. When you do a mp3 conversion it’s not only the top end frequency that goes (although a top cut-off of 16 or 17kHz is not significant for most adults), but frequencies well down in the audio range are lost or attenuated, the effect of which is some level of distortion. 128 and 96Kbps may be just about bearable if you’re listening on low-end playback, but when you get down to 64-32kbps range you’re definitely in the voice (radio and telephony) recording range – but even that low range can have an application in recording tunes – of which more below. When you get down to 128kbps (the “near-CD” quality beloved of mp3 file purveyors on the internet) even my old ears can tell the clear difference between that and 192 and higher. I think you’d have to have an extremely good ear and absolutely top-of-the-range audio equipment to notice any significant difference between the source (1411kbps) and 320kbps – and possibly as far down as 160kbps (iTunes suggests 160 or 192 for most purposes). Here are some of the results (the column tabulation may not show as it should):

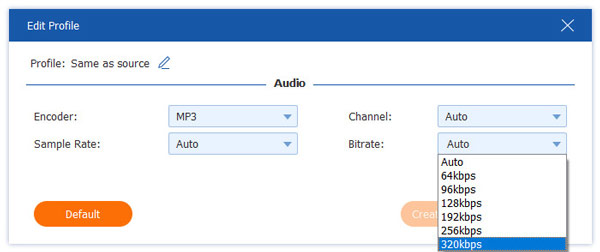

I made several mp3 versions of the sample at different bit rates, using eRightSoft’s “SUPER ©” media converter, and compared the spectral frequencies of these mp3 files on screen using CoolEdit.

Using CoolEdit’s spectral frequency analyzer the frequency and harmonic content of the music was very obvious on screen. I copied the extract onto my computer using standard audio properties - bit rate 1411kbps, audio sample rate 44kHz, audio sample size 16 bit, and 2-channel stereo.

128 KBPS VS 320 KBPS FULL

I chose this because the harmonic content of her playing on her Guarnerius violin on occasion extends beyond 20kHz (about the top limit for a quality CD), and her playing is accompanied by a full classical orchestra. For my source I used a few seconds of a CD recording of the violinist Sophie Mutter playing part of Mozart’s A-major violin concerto. You may not be aware of this frequency loss if you’re listening on low-end audio equipment, but it is very definitely there.įor my own interest I’ve done a little research into this effect. Mp3 is very convenient for this but is what is known as a “lossy” format – which means the price you pay for a compressed file size is a loss of frequencies throughout the audio spectrum of the recording. Most of us at some time or other convert an audio recording to the more compact mp3 format for storage, or for play-back on mp3 players, or for sending audio files through web-space.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)